[ad_1]

Every year local government bodies or councils across Britain contact residents, asking them to update their voter details on the electoral register if these have changed.

To do so, residents are asked to visit HouseholdResponse.com, a domain that looks anything but official and has too often confused people, who mistake it for a scam.

What’s worse is, failure to respond to this notice by visiting the website can, at least in theory, lead to a criminal penalty—a fine up to £1,000, according to the Electoral Commission website.

This can spark a sense of urgency and anxiety among people, and is a weakness that scammers could exploit.

‘Household Response’ not a household name

Last month, councils across England and Wales began contacting property occupants, asking them to update their voter records by visiting HouseholdResponse.com.

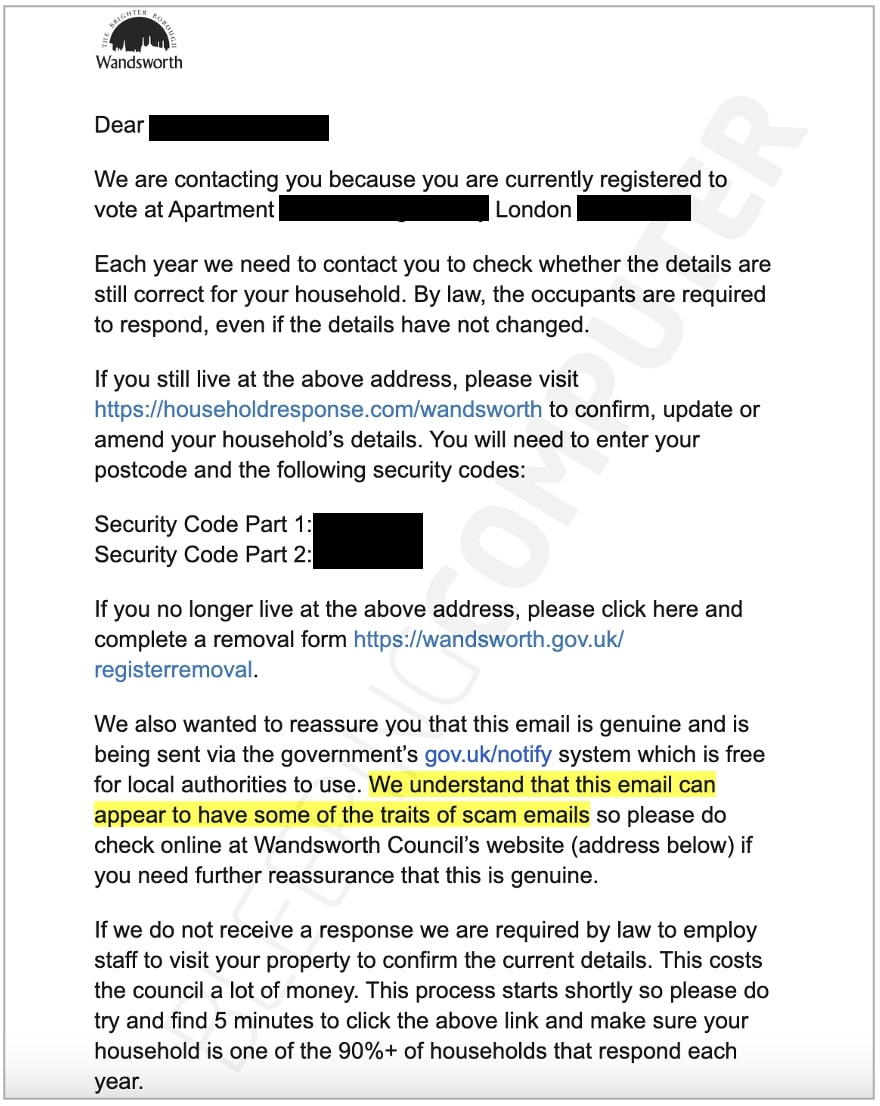

These notices, sent via postal mail and email, state the name and address of the resident who may be eligible to vote, along with a 2-part security code that needs to be entered on the Household Response website for authentication.

The resident is then asked information about the people who live at their address, and if these people (including themself) are eligible to vote.

Failure to respond to the notice or providing inaccurate information can result in a £1,000 maximum fine, according to The Electoral Comission.

Suffice to say, the choice of domain, HouseholdResponse.com has frequently left residents confused and worried if the correspondence is a scam.

“It really is scandalous that in 2023, councils require electoral registration/confirmation to happen on householdresponse dot com rather than an actual trustworthy .gov site,” states London-based software developer, Pranay Manocha on social media:

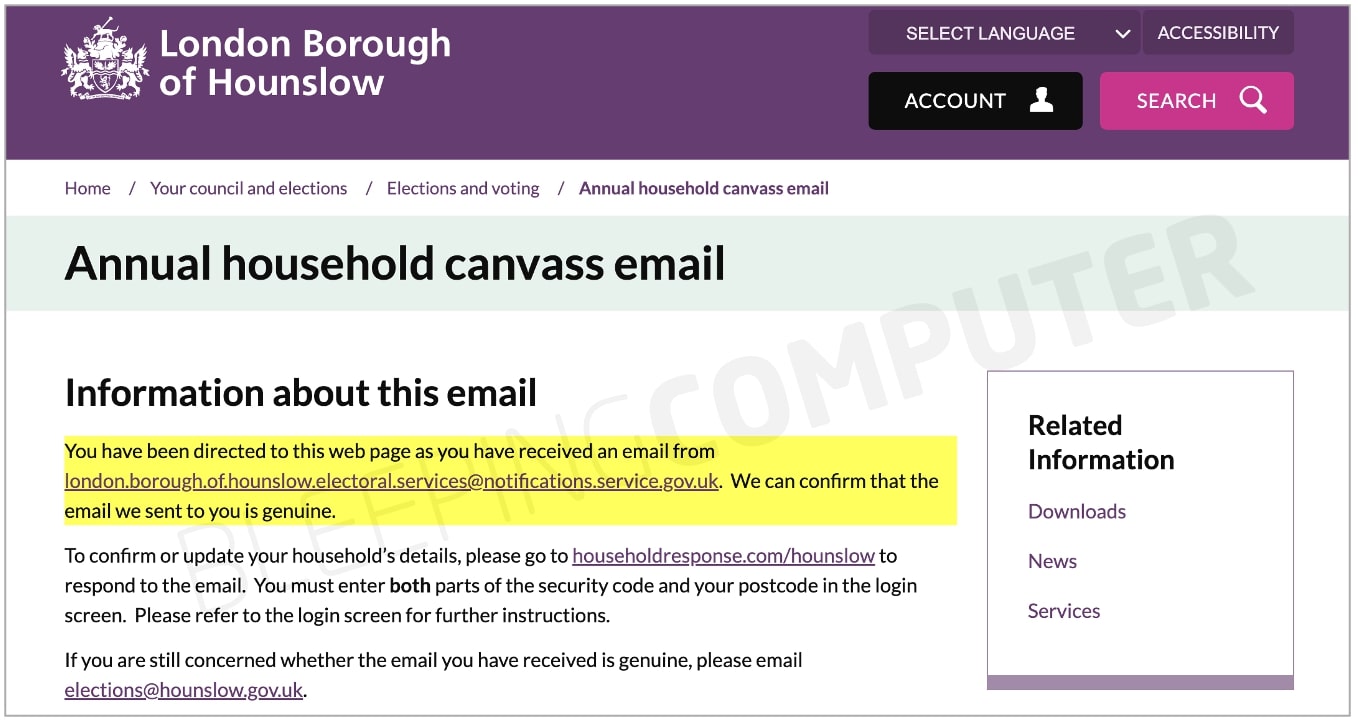

In the past, others have also chimed in. And councils have had to step in to confirm that these notices are indeed genuine:

“Each year the council’s Electoral Registration Officer (ERO) must conduct an annual canvass of all households to check that the information on the electoral register is up to date,” a Buckinghamshire Council representative explained to the resident at the time.

Furthermore, the rep explains, because voter records on the “open register” are often reported to credit bureaus, and used for online identity verification, those who do not keep their details up to date could face problems when applying for credit or utilities:

“You may also have difficulty in getting credit for mortgages, credit cards and mobile phones, as the register is often used to carry out credit checks.”

“It is a legal requirement to confirm details relating to your property. If you do not respond to the annual canvass you may be unable to vote in elections.”

But, the resident did not seem convinced at the local authority’s explanation and doubled down.

“I will be making a complaint to the [Information Commissioner’s Office] about this,” responded Preston-based Christian Ashby.

“It is irresponsible to encourage citizens to click links in emails that are not identifiably run by you or a related authority, especially when PII is at stake.”

Even councils admit the notice looks fishy

It’s not just the people—even councils sending these notices out admit that these bear an aura of suspicion, and have gone an extra mile to reassure citizens.

(BleepingComputer)

To help weed out any confusion or anxiety among residents, some councils even include a link to their website in these notices attesting to the “genuine” nature of the domain.

Similar advisories have been issued by Leeds, Rushcliffe, Chemlsford,.. you get the idea.

This bureaucratic process of confirming who is eligible to vote at each residential property is referred to as “annual canvassing.”

There are good reasons for the annual canvass.

Britain’s criteria for who is eligible to vote is rather broad, unlike what may be the norm in the US, Canada, and most nations.

To elaborate, you need not be a British citizen to cast vote in the UK. Citizens of Ireland and qualifying Commonwealth nations (which is a long list comprising Australia, Canada, India, Jamaica, Pakistan, Singapore…) who are legally residing in Britain are also eligible to vote in all elections. (It’s a bit more complex for EU citizens).

It therefore becomes vital to keep the electoral register up to date at least once a year.

Safeguarding against scams

Used by more than 250 councils across UK, the Household Response service is hosted and maintained by a private company called Civica Election Services (CES).

But that’s not a convincing explanation as to why the service can’t be configured to use a .gov.uk domain.

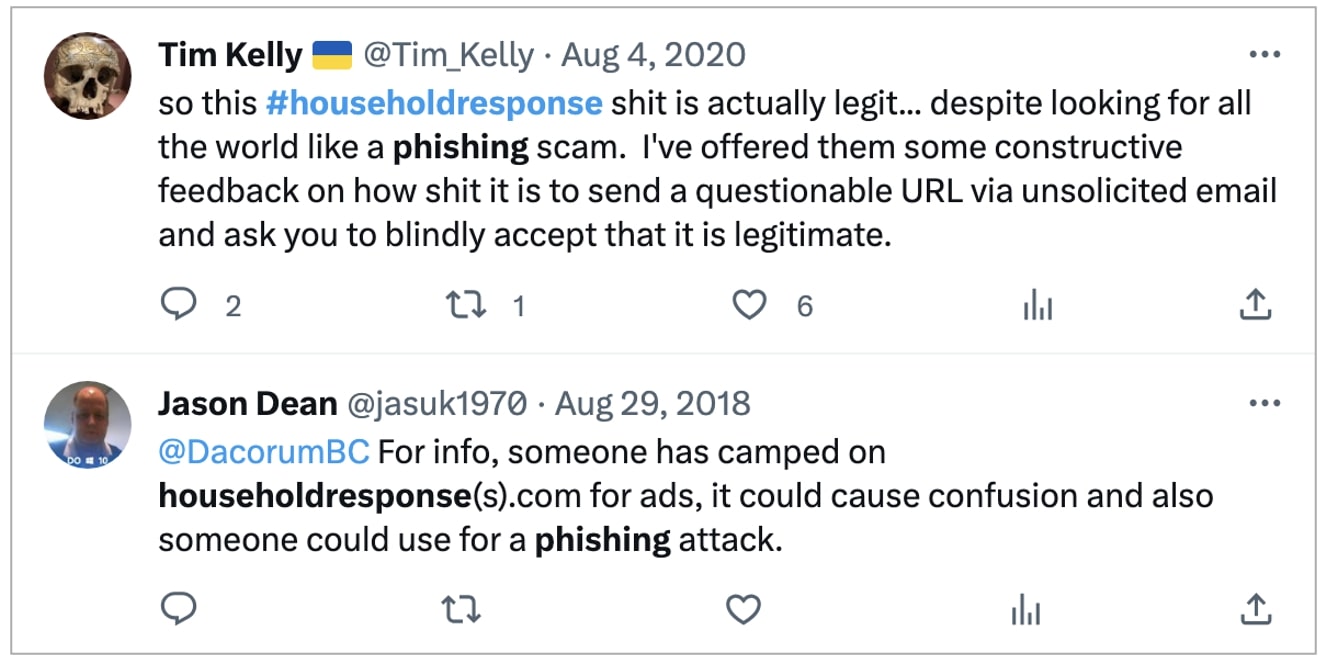

Some caution, how the confusion associated with the domain can be leveraged by scammers to create lookalike phishing domains:

“For info, someone has camped on householdresponse(s).com for ads, it could cause confusion and also someone could use for a phishing attack,” cautioned UK-based Jason Dean, who works in the banking software industry.

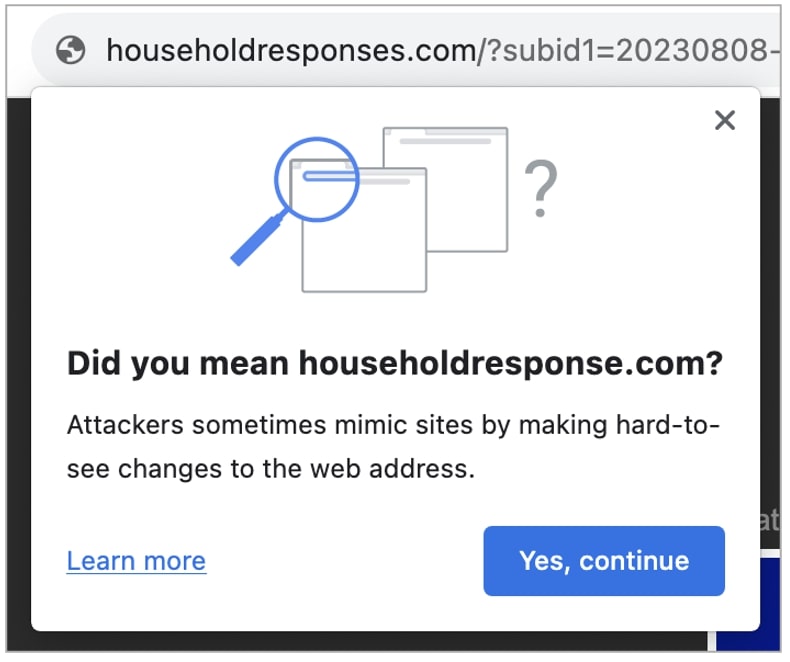

Thankfully, at the time of writing, the domain householdresponses.com (with a trailing ‘s’) leads to a generic parked page, BleepingComputer confirmed.

Browsers like Chrome even warn the visitor if they meant to type the legitimate householdresponse.com instead:

Governments around the world frequently contract third-party software vendors to provide web portals and domains for their services—such as for collecting parking fines.

But, too often, the choice of non-government domains can make a web portal hard to distinguish from illicit websites setup by threat actors.

When receiving correspondence via text, email, or postal mail that claims to be from the government, first ensure that the website or the phone number you are being directed to is endorsed by your local government authorities or council by visiting the council’s official website directly.

[ad_2]

Source link